“Calle Pellaires”, I instruct the taxi driver who picks me up at the airport.

“To Mariscal’s place?” he asks.

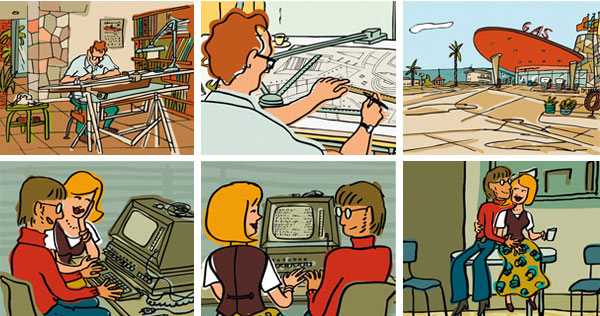

In Barcelona, even taxi drivers know him and this despite the fact that he is only a designer. And designers − with the exception of Starck, who is, above all, a great communicator − are not generally well-known by the man on the street. What has Mariscal, whose 100th anniversary will be in 2050, done to have become so famous? He has done a great many things, to be sure, within different disciplines and without showing any preferences. And he has undertaken them all with enthusiasm and confidence. Graphic design, design for the home, painting, animation, illustration, sculpture, interior design, city planning, landscape gardening, horticulture… they have all formed part of his professional and personal trajectory. “He derives equal pleasure from admiring a painting by Klee, riding a roller coaster, or driving a scooter along a coastal highway. Each image registered in his retina, each ordinary experience, is processed in an unbiased way in his memory” (Àngels Manzano, Mariscal. Ultimas cosas). It could also be argued that, in addition to having done so many things, Mariscal is so well known and loved because he represents the Spanish creative soul, that combination of vitality, sentimentalism, surrealism and abstraction that is a feature of the great Spanish masters.

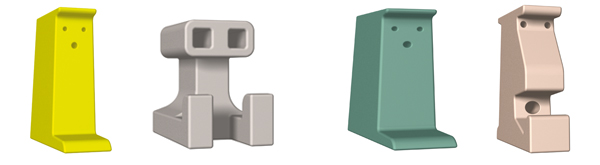

Me too collection, Magis, 2004.

Me too collection, Magis, 2004.

It is difficult to discuss design with Mariscal, to get him to stick to one question. What’s more, he regards questions in general as being stupid. If somebody asks, it is because he hasn’t understood. On the other hand, his projects talk loud and clear. Like a juggler, he throws arguments up in the air as he walks across his studio and stops in front of a design, an object, a book. Flying like an insect from one idea to the next, Mariscal recites stories. Because everything he does has a story behind it. A long story, full of episodes. And every stroke he traces, albeit giving the appearance of being the fruit of instinct, condenses an experience; it is the simplification of an existential complexity that describes a world of relations. He has a gift for synthesis, a synthesis that is comprehensible, one could even say perceptible, on first contact. And, hence, playful, given that games, as children well know, form a system of learning through experience. He talks of the jasmine which he has personally planted in the courtyard and which now climbs up the façade of the ancient tannery where he has set up his studio. Here we find orange trees, lemon trees and bougainvilleas too.

.jpg) Buganville, Mariscal Studio (left) Mariscal Studio. Stop war. All you need is love (rigth).

Buganville, Mariscal Studio (left) Mariscal Studio. Stop war. All you need is love (rigth).

There are flowers year round, as well as a great many insects and birds. And he derives great pleasure from naming each one of them. “Plants, insects and birds,” he says, “as if this were an island meant to show us that we can live in the midst of nature even on a paved city road.” He is proud of the space he has created. A human place, inhabited by artisans and artists, that has not been denatured and where he tends a vegetable garden filled with aromatic herbs. A happy oasis where he works, in a natural and direct way, with thirty collaborators, who form a kind of extended family. And where he receives us without further ado. The traditional bronze plate is missing from the door, its place taken up by an inscription, sprayed on like graffiti, that reads: “Mariscal Studio. Stop war. All you need is love.”

The traditional bronze plate is missing from the door, its place taken up by an inscription, sprayed on like graffiti, that reads: “Mariscal Studio. Stop war. All you need is love.”The packed tables brim over with designs, clippings, posters, illustrated books. At the studio they are working on the portrait of Prince Philip and his fiancée, which will be published by El País on the day of the royal wedding. A contemporary Velázquez, Mariscal is the portraitist of the royal family, and he goes to great pains to modernise the image of the prince, who always dresses formally. He stops next to a book for children, Lula goes to the Sea, and amuses himself by commenting on its illustrations, describing the Mediterranean nature which he has represented in it. He lists plants, animals, insects. As he does so, he evokes the perfume of the pine trees and the aroma of the waves that crash against the reefs of Formentera. Like a naturalist, with the thoroughness of a botanist, he represents each detail, even if his designs are never calligraphic, encompassing nature in its totality. The pine tree, traced out with only a few lines, manages to represent the idea of Mediterranean nature, condensing all its colours, fragrances and moods. He discusses the illustrations as if he were reading to his twin daughters in bed, before they go to sleep. He repeats himself, because children love hearing the same story over and over again. His designs, including those he makes for children, are not awkward, but rather elaborate.

They are the result of long hours of careful observation: polished and ironic. And irony is a feature of maturity. They represent life in all its facets. They include animals and plants, because they form a part of life. “Even humans can behave like animals at certain moments,” he explains. “I am tame, but I can also become a tiger. Drawing animals − he concludes − means choosing life.” Mariscal expresses himself through images. And he is generous with his images. Although he is frugal with his theories. “I am not like those designers who always have a statement ready for every design they make. I don’t like talking about my work. I am very lazy. But I like other people’s designs, because they give the appearance of being finished, perfect. I almost hate mine.” He talks highly and respectfully of his colleagues and clients, a rare case in a world that looks in on itself, dominated by narcissism.

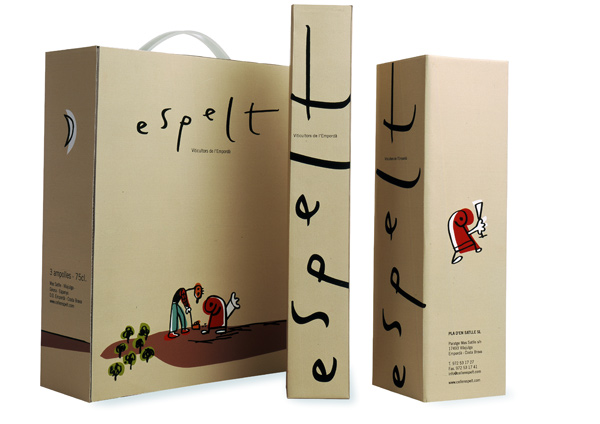

Espelt Winery, 2003.

Espelt Winery, 2003.

On the top floor of his large studio, which is laid out on two open-plan floors, there is a door that always remains closed. It leads to the area where he keeps his files. A large room full of boxes, rolls, fabrics, packages, etc., where he keeps everything he has produced in his lifetime, from the Memphis stool to Cobi, the mascot of the Barcelona Olympics, including the rugs he designed for Nani Marquina, the armchairs for Moroso, the cuddly toys for Cha Cha, the chairs for Amat and Andreu World, and some paintings. A huge repository of memories and experiences where everything can be touched; where the designs are kept or, better said, piled up, covered in a thin layer of dust, like the vestiges of an emotion, instances of a personal history, instead of being catalogued and ordered like the records of a professional career.

Mariscal always represents life and the love it brings him. Each of his works reveals, first and foremost, great affection and respect for the subject of the project: if he chooses to design the corporate image of Espelt, a wine from Ampurdán, the region where Cadaqués is located, it means that he loves its taste, that he is in good terms with its producers, that he appreciates their work. It means that he shares their motivations and aspirations, that he has decided to involve himself, from an emotional viewpoint, and that he intends to walk besides this particular wine on its road to the success it deserves.

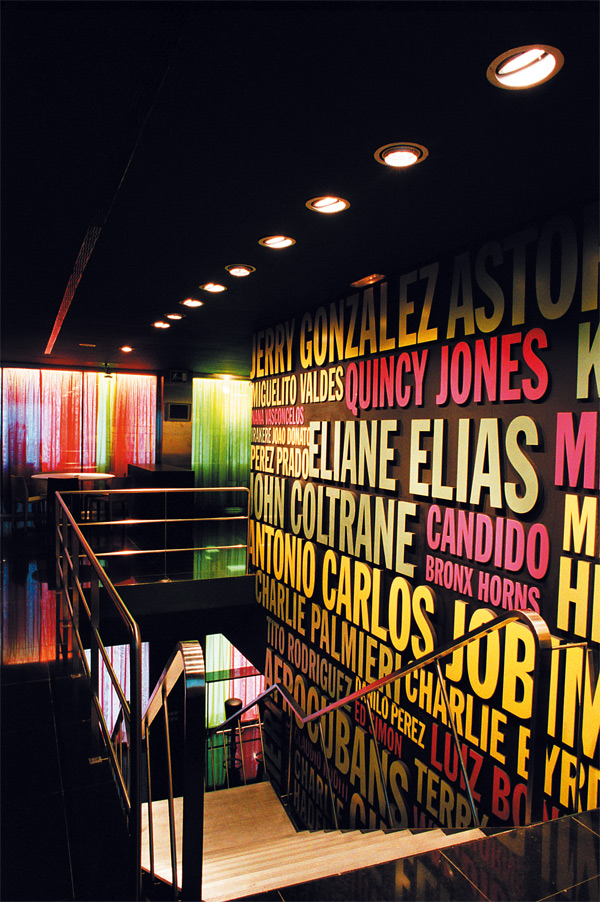

Calle 54 Club, 2003.

Calle 54 Club, 2003.

Calle 54 Club, 2003.

Calle 54 Club, 2003.

One must let him follow his own line of thought, talk about his own thing: about his children, his partners, his friends and, perhaps, his projects too, in order to understand the narrative and emotional component of his work. Because each of his works opens up a horizon. Calle 54, a club in Madrid where he painted a series of murals on which the names of different musicians were inscribed, is evocative of Jazz melodies. “You name them,” he observes, “and they turn up, in spirit, to help you hear their music.” The Felisia theme park designed by Estudio Mariscal, Alfredo Arribas and Dani Freixes, located in the Puglia region next to Taranto, shows the archaic dimension of a made-up Mediterranean civilisation, the Felisis, happy idlers that are always found “resting” under a palm tree.

The educational section of la Caixa’s Science Museum at the Tibidabo recreates a somewhat surrealist voyage through the experiences of space, time, sound and smell. Its astonishing features do not derive from the technical equipment, but from the space itself, designed as a succession of emotional flashes − water, wind, smells, sounds… − which are experienced first-hand.

Barcelona Science Museum, 2004.

Barcelona Science Museum, 2004.

And his graphic designs, comics, animations, corporate image designs (the range of works and acknowledgements is much too long) always send out a moral message. His fantastic bestiary is inhabited by ethical characters that invite us to fraternize, to act responsibly, to protect nature. These strong-willed, occasionally irreverent characters immediately feel like friends.

They are liked even by adults, who perceive in them an aesthetics that goes beyond mere figurative skill and sends out an emotional and intellectual tension. Julián, for instance, the cuddly dog he designed for Cha Cha − a toy manufacturer based in Barcelona who entrusted Mariscal’s pencil with the task of renewing his range of felt animals − has had enormous commercial success at Driade, a refined interior design shop in Milan that does not normally sell toys. The posters he has thought up for Barcelona’s Boat Shows portray the sea as a place that must be respected: a mass of people that love the sea and want to protect it from being contaminated.

Barcelona City Council, 2003.

Barcelona City Council, 2003.

The bright Santa Clauses that were placed along Paseo de Gracia during the Christmas season of 2003, featuring the Muslim half-moon, were an invitation to tolerance and cultural crossbreeding, at least over the holiday season.

Defining Mariscal as an illustrator and graphic designer, even when his production in this field is enormous, would be restrictive. He must be regarded as a sculptor, painter, textile designer, for both the world of fashion and decoration, flooring deviser, interior decorator and designer at large. His experience with Memphis, in the early eighties, in Italy, still sticks to him like a gluey tag. He does not like to hear himself defined as “one of the Memphis” designers. He feels it is simplistic, particularly since he has also executed a wide variety of designs for Akaba, Bidasoa, BD Ediciones, Santa & Cole, Moroso, Nani Marquina, Cha Cha, Pamesa, Worwek, Equipaje, Amat, Alessi, Sangestsu, Rosenthal, Swatch… And not only pieces of furniture, but also lamps, felt toys, suitcases, rugs, pieces of china, fabrics, watches, bathroom fittings, etc.

Hewlett Packard, 2004.

Hewlett Packard, 2004.

He is very enthusiastic about his recent participation in Mags’ new collection of Me too children furniture. The tables at his studio are covered with photographs of the stand (filled with happy and colourful little monsters) which the Venetian company set up at the Milan Furniture Show held in April 2004. His dog- and cat-shaped chairs have already become a prototype, and Mariscal is already thinking of crocodiles and other animals that can be turned into new chairs and benches.

Defining Mariscal as an illustrator and graphic designer, even when his production in this field is enormous, would be restrictiveHe is also working on a deck chair for Amat, a mass-production piece made of injected-plastic that features a light ornamental motif − fretwork that is reminiscent of plaited wickerwork − to make it more attractive. And he is studying a complete line of chairs for Andreu World. Indeed, chairs were the subject of one of his latest shows in Bilbao, Mariscal: Últimas Cosas (Mariscal: Latest Objects). Though the world is filled with chairs, and though manufacturers continue spewing out chairs, Mariscal, through his painted-iron sculptures − that summarise in a happy gesture the identity of some archetypal chairs − has managed to create something new.

Through a sign, he has managed to extract the concept of form, revealing the dynamic soul of chairs, often imprisoned in a corset that mortifies their flesh. Poetic “X-rays” of chairs, a kind of invitation to contemplate the objects around us, beyond their appearance, an incitement to catch their spirit. Sculptures that can be regarded as an incursion into the origins of the design, that reveal his brilliant penchant for synthesis. A synthesis that is not translated into classical minimalist reduction, but which rescues formal redundancy in a smooth stroke.

“I never know what to answer when asked to define design,” he says. “I think it brings about social improvement, it contributes to make our ordinary surroundings more pleasing. I have just bought a Kartell trolley, designed by Antonio Citterio, and I get the feeling that dinner with my wife is more gratifying now. It is elegant, it is easy to move, it helps to transport food… This is why I always look around me a full 360 degrees,” he adds, “and I try to evoke ironic and smiling forms that make the ordinary less monotonous, more enjoyable, revealing its hidden and unexpected aspects.” “I would like to open people’s eyes, so that they learn to see not only the functional part of an object, but also its symbolic and poetical side.” This is why he has created these painted-iron sculpture-chairs, chairs that were not designed to be sat on but which nonetheless continue to be chairs, representing as they do the cultural imitation of a chair and revealing the noble soul behind the concept of a chair. Their arabesques raise the ordinary to the level of the sublime and, at the same time, representing known forms that are not abstract, turn the sublime into something that is close and accessible.

Me too collection, Magis, 2004.

Me too collection, Magis, 2004.

In Italy Mariscal bought all of Bruno Munri’s books for children, which are currently being re-edited by Corraini, the refined publishers from Mantua. He regards him as a great master. True, they belong to different generations and schools, Munari’s being more conceptual, Mariscal’s more intuitive, but they have in common certain innocence and a capacity to feel surprised by nature. It is no coincidence that they have both designed animals. Zizi, Munari’s articulated monkey, which received the Compasso d’Oro in 1954, could be Julián’s forebear. They are both capable of attracting the attention of children and adults alike. And they are not only toys; they are also symbols of a way of seeing the world through eyes that steer clear of disillusionment.

Artícle published in Experimenta 49.