What a good start to 2005 for Reza Abedini. he took a gold award in Hong Kong’s poster triennale, one of many poster events currently enlivening the graphic design scene in the far east (from tokyo to Pekin via Taipei), open to entries from visual cultures beyond the border (or, better said, borders). and entries come not only from the west, but also from the middle east – a territory that (supposedly global) ‘chat’ culture seems to show little inclination to get to know or understand more about.

Any assessment of Reza Abedini must take account of two premises. The first of these is of a strictly professional nature: while it is a fact that his poster output is prolific and superb, it would be an injustice to their author to overlook his work in other areas of graphic design. These range from publishing books and magazines to designing marvellous logos (and their associated images) in which Arab script regains all its visual coefficiency – the properties that traditionally adhere to it and which transform it into image, decoration and decorative motif, serving to represent the word of Allah in an iconoclastic religion in which (as in others) representations of the deity are prohibited.

The second premise is the obvious point that the anti-Arab campaign organised after the Twin Towers attacks is threatening to create a ghetto around a culture to which we not only owe an enormous historical debt (we know Aristotlethanks to the Arab philosophers, and the Moors brought us paper in the 13th century), but one which also mirrors our own antinomies in western society. Abedini functions as an ambassador for contemporary Iranian culture given the degree of visibility he has achieved. That said, though, this is probably not as true of him as it is of Marianne Satrapi (though she does live in Paris), whose comics have amazed Europe in recent years; or Shirin Neshat, an artist famous for her videos and photographs, who also lives abroad, in New York.

Reza, on the other hand, lives, works and teaches in Tehran. But actually, it is Iranian graphic design that has taken the initiative in showing itself to the world, with exhibitions and congresses such as the Mois de Graphisme in Echirolles (France) in 2000; the Centre de la Gravure et de l’Image Imprimée in La Louvière (Belgium) in 2004; and Tipografia e grafica dell’Iran, in Adria (Italy) that same year. These initiatives reflect a wealth of activity, expressed in Iran via a lively International Poster Biennale, and protected by a professional association (the IGDS, Iranian Graphic Designers Society), which is a member of Icograda.

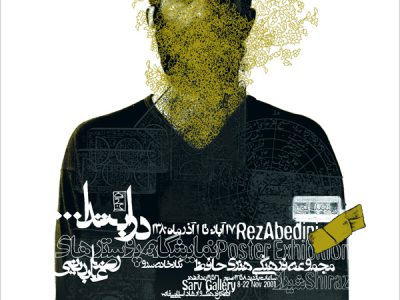

This last, redundant piece of information serves merely to disprove any notion that we might have happened upon exotic, surprising talents. Abedini has a sound design and art background (a diploma in design and a degree in painting), professional experience exposed to the rigours of the job, and an interest in posters which – and I cannot stress this enough – he also uses as an opportunity for visual experimentation. What characterises his work is his use of visual elements perceived as graphic elements. Writing, photographs, figures, portraits, drawings … each of these twodimensional objects has, initially, a graphic function and only then a referential one.

It is therefore the composition that bears the meaning: syntagma prevails over paradigm, metonymy over metaphor. This explains the temporal character of Abedini’s images, which hold our gaze for a long while. It seems reasonable to suppose that this capacity for privileging the graphic sign is the product of a habit of writing: the calligraphy of Arabic script is an example of harmony and of an emotive (but also semantic) interpretation of the sign. After all, the very word ‘graphic’ derives etymologically from the Greek graphein, meaning ‘to write’.

Published in Experimenta 51.