Willem Gispen, a trailblazer in his double role as designer and manufacturer, decided to go for tubular steel and serial production and, in so doing, he chose to forgo aesthetic pretensions in his industrial creations. A well-known activist in the artistic and business circles of his time, Gispen was one of the individuals responsible for promoting the social values of the arts and crafts movement. The incorporation of his designs into the Dutch Originals replica catalogue is proof of the validity of his work.

The firm

In 1916 W.H. (Willem) Gispen (1890-1981) took over a small smithy in Rotterdam. Gispen, who had trained as an architect at the Academy of Visual Arts in Rotterdam, was at first assisted by two employees. Initially, the workshop manufactured a type of wall-rack system consisting of wall bars and consoles. Financed by the sales of this product, the workshop was able to turn its hand to ornamental wrought ironwork designed by Gispen himself or by architects from his network of contacts. The buyers of this kind of work included architects, in the first place, and well-to-do clients who could use these products in their buildings and in their homes. Besides ornamental wrought ironwork, from 1919 on the firm (Gispen’s Metalwork Factory) began to produce copper, brass and bronze products, such as fireplace accessories, lamps, clocks, illuminated signs (with stained glass) and even wooden furniture. Having recently moved to bigger premises, the factory already had 21 workers on its payroll, a number that would grow to as many as 150 employees in the 1930s.

In 1919 Gispen experimented with his first artistic series production: cast brass lamps with a bronze patina. He did this trial run because he knew there was more of a future in serial production than in expensive one-offs. Ceiling and wall lights in moulded copper, with a frosted glass shade, followed in 1923. This change towards serial production was related to the ideas on functionalism held by Opbouw, the Rotterdam circle of architects of which Gispen was a founding member. In 1926 he began the standardized production of lamps, based on modern German and American theories on lighting technique. These he sold under the brand name of Giso (a trademark deposed in 1927). From that date on, Gispen sought a house style of his own. Advertising and printed matter, products and, as of 1928, showrooms, all had to correspond in style. He even went as far as to design a base burner especially for the display rooms in Amsterdam and Rotterdam. There was a fairly large serial production of Giso lamps, some orders requiring a thousand copies of a single lamp model. By standardizing as many parts as possible, Gispen was able to make numerous combinations with a limited number of parts.

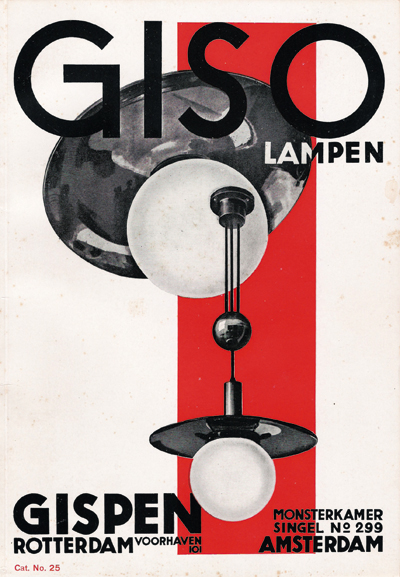

Giso lamps poster, 1928.

The Gispen factory began to experiment with tubular steel furniture in 1927. In 1929, backed by a large order from the Van Nelle Company in Rotterdam, Gispen succeeded in manufacturing this kind of furniture in quantities comparable to those of Giso lamps. To better reach and serve the foreign markets, in addition to the display rooms in various Dutch cities, Gispen opened showrooms in Brussels, London, Paris and Cape Town. The Paris showroom brought him commissions for the likes of the prestigious Normandie ocean liner and the Paris residence of the Aga Khan. In 1934 the firm moved to Culemborg, where it still stands, although it only produces office furniture these days.

Networks and contacts

Gispen knew many important people in the areas of culture and industry as a result of his being an active member of several associations, amongst them Opbouw, the cultural society known as the ‘Rotterdam Circle’, and the union of idealistic manufacturers which went by the name of the ‘Society for Art in Industry’. All of these organisations were relatively young, having been established recently, often in response to the dissatisfaction felt with existing traditional groups or associations. Their members regarded one another as fellow believers in modern ideals. Gispen received many commissions through this network of acquaintances, and his factory, in turn, used the services of many of those he met. For example, he commissioned a number of talented photographers to take pictures of the manufacturing process and finished products; these included Jan Kamman, Paul Schuitema, Eva Besnyö and Cas Oorthuys, all of whom took part in the modern movement. Together with Kamman, Gispen designed the famous Giso lamp poster of 1928, in which Gispen combined his own layout and lettering with a photomontage by Kamman. In 1930 Schuitema designed several catalogues, among others for Gispen; before and after that time Gispen designed all the company advertisements himself. This was another area in which Gispen showed remarkable talent, and his mastery of two- and three-dimensional products made him an all-round designer. Gispen became good friends with the architects L.C. van der Vlugt and J.J.P. Oud.

Proof of the cover of Gispen’s tubular furniture catalogue Nº 52, 1933.

For their architectural projects, which were to reap fame beyond Dutch borders, these men selected lamps, furniture and other items from the Gispen collection. Examples of their buildings include the Van Nelle Factory (1929-1930), regarded as ultramodern in its day, which was furnished with Gispen furniture, lamps and other accessories, and the model housing designed by Oud and equipped with Giso lamps for the Die Wohnung exhibition, together with the model district of Weissenhof (1927) in Stuttgart. The exhibition and the housing estate are considered to be the international breakthrough of functionalism. At Die Wohnung, Gispen was given the chance to display his Giso lamps in the exhibition hall. Giso lamps were open to view alongside lamps designed by the Bauhaus instructor Marianne Brandt and the Danish architect-designer Poul Henningsen. Gispen’s attendance to the show provided him with new contacts. The

German architect Adolf Rading, who had designed housing for Weissenhof, ordered Gispen furniture in 1930 for his Rabe House in Zwenkau. Gispen asked Mies van der Rohe for the loan of an object which the latter had on display in Stuttgart: a cantilever chair, greatly admired by designers. Gispen wanted to put it on show in the Netherlands at the Artless Implements exhibition which he had organised for the Rotterdam Circle and which was to be held in late 1927. In this way, Gispen gradually learned to move among not only the Dutch but also the European avant-garde.

Stylistic development

Stylistic changes in Gispen’s designs were closely connected with what he saw and read about art. In 1910 he became acquainted with the ideals of Ruskin and Morris on one of his visits to England. This prompted Gispen to abandon his plans to become a teacher and to study architecture and design instead. The making of one-offs was a late departure from the Arts and Crafts movement, lacking its specific social objectives. Gispen perceived an appreciation of the beauty of machine products in Berlage’s version of the ideas of Gottfried Semper. Reading De Stijl, a magazine of the visual arts, and discussing the latest architecture and design at the Opbouw meetings strengthened Gispen’s recently-awakened admiration for technical production without aesthetic intention. Gispen saw the sculptural language of constructiv-ism and L’Esprit Nouveau derived from cars, trains, ocean liners and aeroplanes, such as advocated by Le Corbusier, expressed in the most advanced pavilions at the Paris Exhibition of Decorative and Industrial Arts in 1925. Industrial Rotterdam, with its loading bridges, grain elevators, silos and railway vertical lifting bridges also made a big impression on him. As previously mentioned, Gispen met like-minded designers at the Die Wohnung exhibition in Stuttgart.

The combination of all these impressions found expression in Gispen’s designs. A few of them came close to the original models; his variant on Mart Stam’s cantilever chair was the object of discussion in a lawsuit. Thonet, which produced the original 1926 Stam chair, took Gispen to court but the judge decided that only a technical invention was at stake here. Thonet never applied for a patent, so there were no legal grounds to prosecute Gispen.

Case dismissed.

Ideals and the struggle for survival

Gispen’s ideas on art and industry were closely related to his double role as designer-manufacturer. The dangers of this position were described by design critic Paul Bromberg in 1933: “Gispen’s factory for metalworking is, however, a company that must make a profit and cannot be discriminating about what concerns its sales market; the company must adapt to that market, and mistakes are made because of it that could lead production into fashionable trends. As a business the Gispen factory may flourish, but it will then have lost its cultural significance.” Concessions made to public taste included the textile shades of several Giso lamps. Besides the standard colour scheme (natural for the shade and clear or frosted white for the glass), clients could choose from lemon yellow, ochre yellow and orange for the shades and ivory-tinted, pink and blue for the glass. The textile shades and the extra colours served a single purpose: cosiness. Because of the heavy upholstery used for some of his armchairs and sofas, these were often more akin to comfortable living room furniture than an expression of functionalism.

Chair nº 412 originally from 1932, reedited by Dutch Originals.

Yet if we, like Bromberg, measure the enormous production that took place between 1916 and 1946 (when Willem Gispen left the firm) against its cultural importance, we will see that many of the products were outstanding examples of modernist industrial design, being well-proportioned, well-considered from a functional point of view and having interesting contrasts in material. Most of all, they had a machine aesthetic look, as close to the functionalist ideal as possible. In this sense, Gispen’s best work can compete with that of the leading designers from Germany and France during the interwar period of the 20th century. He ought to be seen as a true Dutch pioneer of industrial design at a time when professional education in the discipline did not yet exist. Gispen set an example with his corporate identity avant-la-lettre and in his double role as designer and manufacturer he was ahead of his time. Today, replicas of his most famous designs (lamps and furniture) are being produced and are evidently selling well.

Published in Experimenta 55.