After years of relative indifference, our industrialised societies suddenly seem to be preoccupied with the risks of climate change. “Zero carbon” is a catalyst for initiatives, and it has brought about projects… Environmental awareness is reaching the decision makers and the citizen. However, identifying the problem does not mean finding a solution… A growing majority of people now believe that the dream world of a consumer society (if indeed one can speak of a dream) is not viable on a global scale, regardless of the progress of green technologies in the coming decades.

We need to change our lifestyles dramatically. But what is a sustainable lifestyle? What will our daily lives become if we agree to change some of our routines? How do we reduce our impact without lowering our living standards? Observations show that growing material wealth and levels of population satisfaction are increasingly uncoupled. Could the pursuit of more sustainable lifestyles also lead to better quality and more satisfaction? In this article we attempt to answer some of these questions. Mainly, we suggest a scenario: the Scenario of Collaborative Services.

“Car-sharing on demand”, “micro-leasing system for tools between neighbours”, “shared sewing studio”, “home restaurant”, “delivery service between users who exchange goods”… This sample of solutions looks at how various daily procedures could be performed by structured services that rely on a greater collaboration of individuals amongst themselves. From this hypothesis, the Scenario of Collaborative Services indicates how, through local. Collaboration, mutual assistance, shared use we can reduce significantly each individual’s needs in terms of products and living space and optimize the use of equipment, reduce travel distances and, finally, lessen the impact of our daily lives on the environment. The scenario also gives an idea of how the diffusion of organisations based on sharing, exchange, and participation on a neighbourhood scale can also regenerate the social fabric, restore relations of proximity and create meaningful bonds between individuals.

Familiy like services.

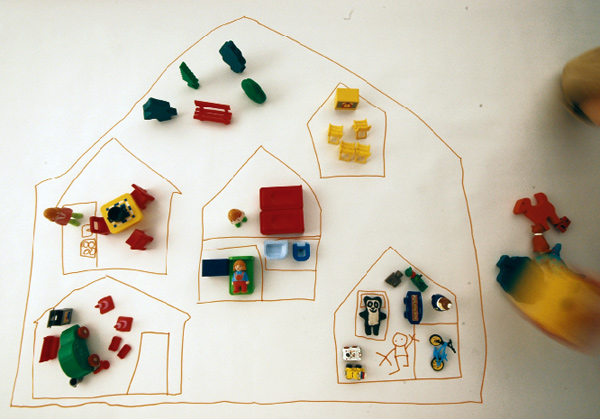

Family like services | This set of solutions evolves from traditional household activities, such as looking after the children, preparing meals, washing clothes or hosting a relative. The principle is to make use of the existing household structure (available space, low-usage appliances, etc.) and the domestic skills applicable (childcare, cooking, washing, shopping). The original family circle extends to include others: mostly singles wanting to live in the same area, an elderly person with reduced mobility or students on their own. Even young couples absorbed by their careers can use certain services and have the benefit of being “adopted” by a family.

.jpg)

Peer-to-peer, Familiy like services. The system facilitates mutual sharing by families in taking children to and from school by synchronizing the children and their chaperones.

Given that, a question has to be raised: if this scenario were to bear the promise of new and more sustainable lifestyles, how could we enhance it? How can we accelerate the diffusion of the services on which it is based?

This article focuses therefore a new design field, which lies at the crossroads of social innovation and design for sustainable developmentThere are certainly some people for whom the ways of living proposed by our Scenario of Collaborative Services are possible and attractive just now. The social, interpersonal and environmental qualities attached to collaborative services surely make them appealing to an increasing number of people who are fed up with over-consumption, who fear rampant individualism and who question the so-called ‘quality’ of life in our modern societies… But however attractive they appear to be, Collaborative Services stand for considerable change in our everyday lives. Sharing, exchanging, pooling together goods and services are activities that require time, organisation and flexibility. In order for them to spread, collaborative services must be quality services. They must be practical and within reach, and they should be malleable according to user imperatives and the different contexts in which they arise.

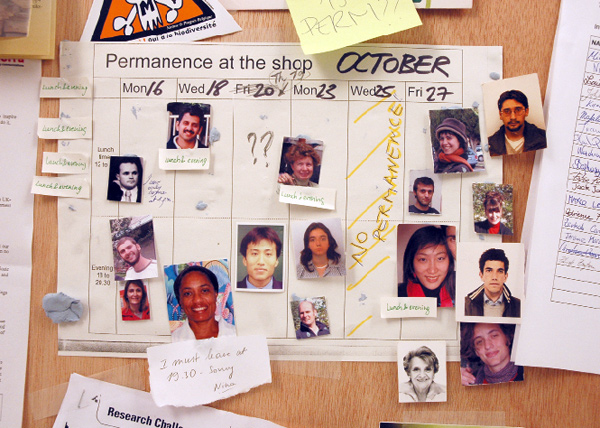

This article focuses therefore a new design field, which lies at the crossroads of social innovation and design for sustainable development. It provides an overview of the research, including case studies of individuals or groups of individuals who have reinvented their lifestyles to come up with new solutions, which are both adapted to their daily needs and more sustainable. These social groups or Creative Communities are part of a deeper transformation currently underway in our society, like the development of a distributed and participatory economy. They give birth to a form of everyday Diffused Social Enterprise. Their diffuse initiatives at the local level provide inspiration for these new Collaborative Services and confirmation of their viability. A strategic design operation turns such discrete initiatives into reliable services that can be accessed by a wide audience and tailored for various territorial contexts.

Familiy Take Away, Familiy like services. The system is based on the principle of a bed and breakfast: one family prepares 3 or 4 extra portions when they cook to deliver to several single people in the neighbourhood.

A new, different and fascinating role for the designer emerges from what has been said here. A role that does not substitute the traditional one, but that works alongside it opening up new fields of activity, not previously thought of. Moving in this new direction, designers have to be able to collaborate with a variety of interlocutors, putting themselves forward as experts, i.e. as design specialists, but interacting with them in a peer-to-peer mode. More in general, they have to consider themselves part of a complex mesh of new designing networks: the emerging, interwoven networks of individual people, enterprises, non-profit organizations, local and global institutions that are using their creativity and entrepreneurship to take some concrete steps towards sustainability.

These innovations are driven more by changes in behaviour than by changes in technology or the market and they typically emerge from bottom-up rather than top-down processes

This article is based on a two-year study realised by a panel of universities, European research centres and international institutions within the framework of the EMUDE research project (Emerging User Demands in Sustainable Solutions) co-financed by the European Commission (see separate box on EMUDE). The results of this research have been presented in two books. The first one: Creative communities. People inventing sustainable ways of living (1) is presenting in details and analysing a selection of bottom-up initiatives promising in terms of sustainability. The second book: Collaborative Services. Social innovation and design for sustainability (2) presents a new conceptual framework and the Scenario of Collaborative Services followed by contributions of the various researchers participating to EMUDE and further elaboration triggered by this research.

Social innovation and designing networks

The term social innovation refers to changes in the way individuals or communities act to solve a problem or to generate new opportunities. These innovations are driven more by changes in behaviour than by changes in technology or the market and they typically emerge from bottom-up rather than top-down processes. Looking to the past, we can see that there tend to be particularly intense periods of social innovation after new technologies have penetrated society, and when there are widespread or urgent problems to face. Over the past few decades, numerous and widely-used new technologies have undoubtedly penetrated our societies creating an as yet largely unused technological potential. At the same time the enormous entity of the environmental and social problems that are pervading our daily lives is apparent to all. It is therefore easy to predict a huge new wave of social innovation (Young Foundation, 2006). Our main underlying hypothesis is that this emerging wave of social innovation could be a forceful driver in the transition towards sustainability.

Community Housing.

Community Housing.

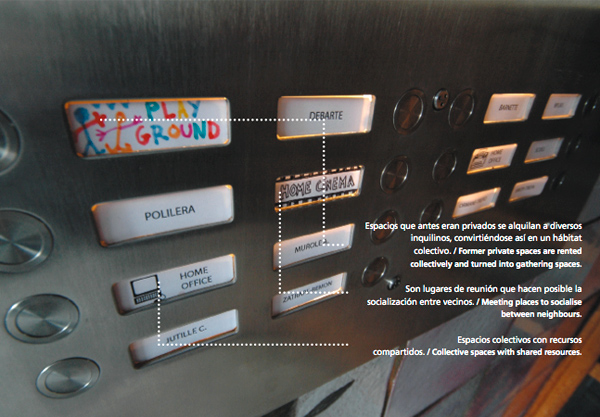

Community Housing | This set of solutions focuses on forms of organization by households that are in close proximity–i.e. in the same village, neighbourhood or building–in order to facilitate the sharing of resources and provide mutual help such as eco-villages or co-housing promoting ecological building, renewable energy production and sharing from gardens to laundry facilities, recreational areas, guest bedrooms. Spaces, both shared and rented, and goods both privately owned and leased out are complementary to private living. They are managed by the community under formal agreements and make daily family life easier, more functional and efficient.

This emerging wave of social innovation could be a forceful driver in the transition towards sustainability

In point of fact, in its complexity and contradictoriness, the whole of contemporary society can be seen as a huge laboratory of ideas for everyday life. People are experimenting ways of being and doing that express a capacity to formulate new questions and find new answers, and this is exactly what we have just defined as social innovation: changes in the way individuals and communities act to solve problems or to exploit new opportunities (Landry, 2006; EMUDE, 2006). Among such cases there are some where this diffuse design creativity has found a way of converging in collaborative activities. For instance, there are: ways of living together where, in order to live better, spaces and services are shared (as in the examples of co-housing); production activities based on local capabilities and resources, but linked to wider global networks (as occurs with certain typical local products); a variety of initiatives to do with healthy, natural food (from the international Slow Food movement to the spreading to many cities of a new generation of farmers market); self-managed services e.g. childcare services (such as micro-nurseries: small playgroups run by the parents themselves) and services for the elderly (such as home sharing where the young and the elderly live together); new forms of socialisation and exchange (such as Local Exchange Trading Systems – Lets and Time Banks); alternative transport systems to the individual car culture (from car sharing and car pooling to a rediscovery of bicycle potential); networks linking producers and consumers both directly and ethically (like the worldwide fair trade activities)…the list could continue (SEP, 2008).

Looking at these cases we can observe that they are diverse in their nature and in the way they operate, but at the same time they also have a very meaningful common denominator: they are always the expression of radical changes on a local scale. In other words they are all discontinuities with given contexts, in the sense that they challenge traditional ways of doing things and introduce new, very different (and intrinsically more sustainable) ones. This is as true of organising advanced systems of sharing space and equipment in places where individual use normally prevails, as it is of recovering the quality of healthy biological foods in areas where it is considered normal to ingest other types of produce, or of developing systems of participative services in localities where these services are usually provided with absolute passivity on the part of users, etc. (Meroni, 2007, Meroni, 2008).

With this initiatives people have been able to steer their expectations and their individual behaviour in a direction that is coherent with a sustainable perspective• Promising cases of social innovation. All of these cases needs analysing in detail to assess their effective level of environmental and social sustainability. However, even at a first glance we can recognise their coherence with some of the fundamental guidelines for environmental and social sustainability. More precisely, the examples we are referring to here have an unprecedented capacity to bring individual interests into line with social and environmental ones. Indeed one side effect of their search for concrete solutions is that they reinforce the social fabric and, more in general, they generate and put into practice new and more sustainable ideas of well-being. In these ideas of well-being greater value is given to the quality of our “commons”, to a caring attitude, to the search for a slower pace in life, to collaborative actions, to new forms of community and to new ideas of locality (Manzini, Jégou, 2003, Manzini, Meroni, 2007). Furthermore, achieving this well-being appears to be coherent with major guidelines for environmental sustainability, such as: positive attitudes towards sharing spaces and goods; a preference for biological, regional and seasonal food; a tendency toward the regeneration of local networks and finally, and most importantly, coherence with a distributed economic model that could be less transport intensive and more capable of integrating renewable energy and efficient energy systems (Vezzoli, Manzini, 2007). Precisely because these cases suggest solutions that merge personal interests with social and environmental ones, we believe they should be considered as promising cases: initiatives where, in different ways and for different reasons, people have been able to steer their expectations and their individual behaviour in a direction that is coherent with a sustainable perspective.

Collectctive Rooms, Community Housing. The principle rests with establishing one or more apartments as common spaces, to allow collective places and slowly evolve the existing building towards a co-housing.

Multi-users Laundry, Community Housing. The system is based on two or three pay-per-use machines, and is designed for collective use, coordinating users and optimizing the maximum use and maintenance of the machines.

Creative communities

Behind each of these promising cases there are groups of people who have been able to imagine, develop and manage them. A first glance shows that they have some fundamental traits in common: they are all groups of people who cooperatively invent, enhance and manage innovative solutions for new ways of living. And they do so recombining what already exists, without waiting for a general change in the system (in the economy, in the institutions, in the large infrastructures). For this reason, given that the capability of re-organizing existing elements into new, meaningful combinations is one of the possible definitions of creativity, these groups of people can be defined as creative communities: people who cooperatively invent, enhance and manage innovative solutions for new ways of living (Meroni, 2007).

A second characteristic, common to these promising cases, is that they have grown out of problems posed by contemporary everyday life such as: how can we overcome the isolation that an exasperated individualism has brought and brings in its wake? How can we organise the necessities of daily life if the family and neighbourhood no longer provide the support they traditionally offered? How can we respond to the demand for natural food and healthy living conditions when living in a global metropolis? How can we support local production without being trampled on by the power of the mighty apparatus of global trade? Creative communities generate solutions able to answer all these questions. Questions which are as day-to-day as they are radical. Questions to which the dominant production and consumption system, in spite of its overwhelming offer of products and services, is unable to give an answer and, above all, is unable to give an adequate answer from the point of view of sustainability.

In conclusion to this point, we can state that creative communities apply their creativity to break with given mainstream models of thinking and doing and in doing so, consciously or unconsciously, they generate the local discontinuities we mentioned before. A third common denominator is that creative communities result from an original combination of demands and opportunities. Where the demands, as we have seen, are always posed by problems of contemporary everyday life, and the opportunities arise from different combinations of three basic elements: the existence (or at least the memory) of traditions; the possibility of using (in an appropriate way) an existing set of products, services and infrastructure; the existence of social and political conditions favourable to (or at least capable of accepting) the development of a diffused creativity (Sto, Strandbakken, 2008).

With this initiatives people have been able to steer their expectations and their individual behaviour in a direction that is coherent with a sustainable perspective

Scaling up

We are not focusing on creative communities and collaborative production and services only because they are sociologically interesting (although they do reflect a significant aspect of contemporary societies). Nor are we doing so because they can generate potentially profitable niche-markets for new businesses (even though this opportunity too could and should be explored). We are interested in them because we think that they can be scaled-up to support sustainable lifestyles for a large number of people. We think, in fact, that they have the potential to become mainstream and reorient the on-going social and economical changes in a sustainable direction. And that they can do so because they are also real steps towards sustainable ways of living that can already be implemented as viable solutions to urgent contemporary problems (of housing, mobility, food, childcare and care of the elderly, health, urban regeneration).

Talking about up-scaling collaborative services, we are not of course proposing “to industrialize” them, meaning to consider them as products that can be mechanically reproduced on a large scale. Our discussion here is about whether and how it may be possible to apply to them a mix of creativity, design and entrepreneurial capabilities and technological knowledge (we can call this human industriosity) to make them more accessible and effective, and so help them to spread on a larger scale. Of course we know very well that in the past century a similar mix of creativity, design and entrepreneurial capabilities and technological knowledge generated, for good and for evil, what we now know as the consumer-oriented industrial system. Our idea is that today, faced with different constraints and opportunities, and looking to different goals, human industriosity can lead in other directions and support sustainable ways of living for billions of people on this Planet.

Extended Home.

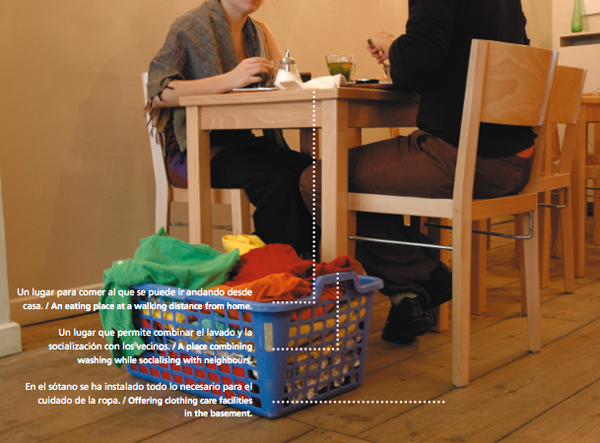

Extended Home | This set of solutions covers services within walking distance that cover certain household functions. For example, public land made available for a community garden or a space where the elderly can gather together for meals. The common denominator is going beyond the boundaries of traditional, private household space. It is a periphery of spaces in the neighbourhood – between public shops, frequented mostly by local people, and private spaces collectively managed – that provide extra services and enrich family life. These areas are perceived as extensions of the family household, resulting in a more friendly and lively atmosphere in the streets.

Replication strategies

Our problem is to scale-up collaborative service ideas, maintaining the small scale and the relational qualities of each concrete initiative. We need to increase the social and economic impact of collaborative services without increasing the dimensions of each one, but rather by connecting them, multiplying their number and creating a large network.

This way of doing can be defined as a replication strategy. Looking to other fields of activities, we can easily discover that this concept is not new and that several replication strategies have been proposed and developed to scale-up services, businesses or even social enterprises.

Even though operating in different contexts and moved by motivations that are very far from those we are referring to here, these existing replication strategies present interesting similarities and offer useful experiences. In particular, we will consider three of them: franchising, mainly used in commercial activities; formats, with reference to the entertainment industry, and toolkits, which is used in several application fields where the do-ityourself approach has been adopted.

These existing replication strategies present interesting similarities and offer useful experiences. In particular, we will consider three of them: franchising, mainly used in commercial activities; formats, with reference to the entertainment industry, and toolkits, which is used in several application fields where the do-ityourself approach has been adopted.

• Franchising.This is a framework of procedures and communication tools to enable local entrepreneurs to start a commercial activity as franchisees of a larger company. This company supports the franchisees with a dedicated set of instruments and requires them to respect a set of procedures and quality standards. In other words, a franchising programme enables several small entrepreneurs to enter into business under the umbrella of the “mother company’s” reputation. They enjoy the reputation of this company and, at the same time, commit themselves to follow the rules that the mother company lays down.

• Format. This consists of a model and a list of procedures, e.g. the model of an existing successful show and step-by-step indications of what to do to replicate it in different contexts. The format producer gives the format purchasers the rights to reproduce the original programme, adapting it to the local specificities. In other words: a format is a programme idea that, extracted from a real experience, can be set up in other contexts. The result is a multiplicity of programmes that are, at the same time, global (the idea is proposed worldwide) and local (in each context it is broadly localised).

Open Handyshop, Extended Home. A shop that offers space to use what it sells: you can find tools and materials like in any other hardware store, but a do-it-yourself space is available in the back where you can get advice from the shop owner.

Washing Restaurant, Extended Home. This solution combines a number of services, just like things take place at home. Here one can come eat while his dirty clothes are being washed: in the basement of the restaurant is a laundry facility.

• Toolkit. This consists of a set of tangible and intangible instruments conceived and produced to make a specific task easier. Each tool can be more or less dedicated to a specific task and the whole kit can be more or less specialised to fit a specific activity. On the other hand, whoever adopts the toolkit can use the different tools in the freest way. And whoever produces the kit takes no responsibility for the results of its use.

The growing number of toolkit proposals is linked to the diffusion in more and more application fields of the do-it-yourself approach. Given these three replication strategies we can immediately see that the first two are, by their very nature far from our interest: not only because they are too strongly commercial and business-oriented, but also because the models they propose are too closed to give the necessary space to the creative groups of people they would (try to) support, and too centralised to permit the relational qualities to emerge.

Nevertheless, we think that they offer some interesting elements for reflection too: the case of franchising, because it deals with enabling small scale enterprises and the one of formats, because it is about replication carried out through the actualisation of ideas. Of course, a TV programme idea is very far from a collaborative production and/or service, and a commercial business under the umbrella of a big brand is even further still. However, in all cases, these experiences indicate that the discussion on how to enable a large number of small enterprises to transform into operative and replicable programmes must start from zero.

Finally, we can consider the replication strategy based on toolkits. It is clear that the notion of toolkit is rather near to the one of enabling solution: the toolkits are offered for certain activities, but they can be interpreted in different ways and used for different goals. Thanks to its openness, the development of an appropriate enabling toolkit is compatible with the nature of creative communities and with the theme of their corresponding collaborative services.

(1) Creative communities. People inventing sustainable ways of living is edited by Anna Meroni with essays by: Priya Bala, Paolo Ciuccarelli, Luisa Collina, Bas de Leeuw, François Jégou, Helma Luiten, Ezio Manzini, Isabella Marras, Anna Meroni, Eivind Stø, Pål Strandbakken, Edina Vadovics. The book has been published by Polidesign, Milano in 2007.

(2) Collaborative Services. Social innovation and design for sustainability by François Jégou, Ezio Manzini with essay by: Priya Bala, Cristiano Cagnin, Carla Cipolla, Josephine Green, Bas de Leeuw, Helma Luiten, Isabella Marras, Anna Meroni, Ruben Mnatsakanian, Simona Rocchi, Eivind Stø, Pål Strandbakken, John Thackara, Victoria Thoresen, Stefanie Un, Edina Vadovics, Philine Warnke, Adriana Zacarias. The book has been published by Polidesign, Milano in 2008.

Published in Experimenta 63.