Patricia Urquiola (Oviedo, 1961), the most international of Spanish designers, lives and works out of Milan. She cites Magistretti, Munari and Castiglioni as her maestros. Of Castiglioni she recalls his most famous lesson: “the imperative of seeking out one’s own poetics, following neither rules nor guidelines”. Author of a prolific list of products and projects, and keeping true to wise teachings, she stays spontaneous and fresh by imbuing her works with her passion for handiwork. Brands such as Moroso, Agape, De Padova, and B&B proudly issue her throbbing and seductive pieces involving a craftsmanship that has revolutionized the “tone” of design.

You only need to scroll quickly back through the recent history of design to realise how certain "revolutions" have to be attributed to movements rather than to the work of any single designer. The Pop Art wave started in Turin at the beginning of the Sixties with Piero Gilardi, Ceretti-De Rossi, Giuseppe Raimondi, and Studio 65, and led to all the objects in the Gufram catalogue. Then came Florentine radical design: Archizoom and Superstudio (1966 – 1972) which made it possible for Poltronova to start producing radical furniture under its visionary CEO Sergio Cammilli. Then came Alchimia, created in Milan in 1976 by Adriana and Alessandro Guerriero, and Bruno and Giorgio Gregori, and which gradually became associated with Alessandro Mendini. Finally there was Memphis, founded by Ettore Sottsass in 1981.

Architecture also played its part: postmodernism and deconstructivism profoundly influenced design. Then when the utopian momentum began to wear off there was a period of style revivals: neo-baroque and neo art deco were reborn in the hands of designers skilful at filtering echoes of the past into contemporary forms that had a strongly emotional component. These too were movements that were not theoretical but stylistic, and that brought together creative people from different fields and backgrounds.

Cocoon bed, Tropicalia collection, Moroso, 2008.

To understand who the designers were who changed the whole tone of design and influenced general taste, as Patricia Urquiola has, perhaps we need to go back to Gio Ponti, not only because of his varied repertoire of forms and his emphasis on the decorative, but because of his general feeling and approach. Patricia Urquiola’s output has profoundly altered the temperature of contemporary design. Even when she creates a single piece, she manages to make it generate an atmosphere. All her work is part of a broader vision of which she controls every detail, following the creative process with passion and meticulousness, making use of creative invention, technology and manual work. She is like Penelope at her loom, weaving warp and woof with female patience and tenacity.

Patricia has feminised design, not in the sense of giving her work a female character in alternative to its predominantly male one, but because there is an intimate connectedness to physical things that women understand better.Patricia has feminised design, not in the sense of giving her work a female character in alternative to its predominantly male one, but because there is an intimate connectedness to physical things that women understand better. A connectedness that in Patricia’s case means being active and vigilant in the act of making things, just in case they might suffer by being out of place. She takes them by the hand and ensures they fit into their context. She works on them with the punctiliousness of an artisan or as one might say, given the prevalence of the female arts in her work, an embroideress; making them look spontaneous, showing the freshness evening gowns used to have when they were starched.

Patricia has brought sewing, embroidery, crochet, and knitting back to life. Everyone in her studio including the males has to learn to use them, not so much to add redundant or banal “feminine” decorations to her designs but to give them a skin that is structural, not just a finish. Worked out by trial and error, this is what gives her projects substance.

Even though her designs sometimes take years to perfect, the female freshness they embody is something she holds dear and doesn’t consider problematic or debasing, but extremely relevant and rewarding. Perhaps this is part of an attitude she inherited from Achille Castiglioni, with whom she graduated in Milan, but it is mainly because she has her own way of seeing things; “another point of view” as Bruno Munari used to say, like the curiosity of children; their marvellous way of seeing a thing in their imagination in some unexpected way, and then manipulating it until it becomes what they imagined.

When Claude Lévi-Strauss (the greatest living anthropologist, who will be 100 years old this November) was being awarded the Nonino Prize in 1986 he made a passionate speech in favour of manual work: "in the societies studied by ethnologists, manual work is associated with ritual: religious acts. The purpose of working with your hands is to have a dialogue with the nature of the materials being worked. Man and nature collaborate in an exchange based on mutual respect, or perhaps even on a sense of deep holiness the man feels for those materials. Through his work, he becomes aware of his role in the greater harmony of all things. This complicity with the cosmos still exists today in the work of the skilled artisan. He is still in direct contact with nature and the essence of things, and he knows he must not violate them; he must do his best to understand them patiently, cautiously trying to get their attention and almost, even, seducing them. Time after time we can observe this ancestral familiarity of the artisan with an inherited body of knowledge, methods, and manual skills perpetually renewing itself as it is handed down from generation to generation”.

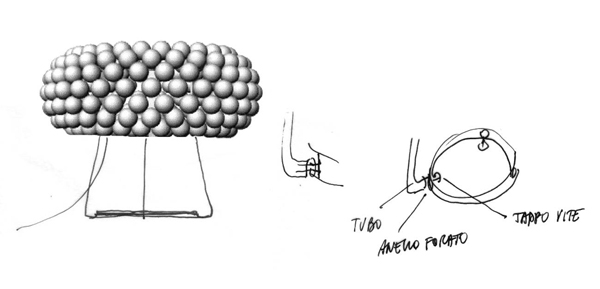

Caboche lamp sketch, by Patricia Urquiola and Eliana Gerotto, Foscarini 2006.

Caboche lamp sketch, by Patricia Urquiola and Eliana Gerotto, Foscarini 2006.

I have never talked about religion with Patricia but I know manual work is a ritual for her too, a ceremony in which she too performs devotional rites, as in her 2008 exhibition of projects for Rosenthal at the Nicola Quadri Gallery in Milan, which took her three whole years to set up. The white porcelain pieces, the preparatory prototypes and moulds all lined up on large antique tables draped with white tablecloths, did indeed suggest the mysticism of the Eucharist: a perfect tableau, precisely setting out the production process step by step. It also had an evocative feel that suggested the devout “respect for doing” that Lévi-Strass described. As an artisan, Patricia doesn’t violate the materials she works with; she respects and seeks to understand them and is particularly adept at seducing them and coaxing unexpected results out of them in ways that are never forced, never unnatural. So many people love her work because of this respect it shows for objects and materials, coming close to them so that she can intimately have a feel for them. Everyone can see how her designs are the product of a dialogue between her soul as a designer and the soul of the material that she has understood and that willingly lets itself be shaped into unexpected forms.

Patricia is as busy and as tireless as a bee: pollinating as she scoops up ideas, things, and thoughts from everyday life: bracelets, stirrers for tea, other ordinary objects.Patricia is as busy and as tireless as a bee: pollinating as she scoops up ideas, things, and thoughts from everyday life: bracelets, stirrers for tea, other ordinary objects; the images of hisorical styles and projects, the applied arts; whatever is in the air around her. Then she regenerates these things. She doesn’t reinterpret them, doesn’t evoke them but recreates them anew, patiently working her way along a path that leads to the birth of something else. That’s why in her exhibitions she always goes out of her way to show how her designs come into being through a process of refining and making perfect. She displays materials, threads, tools, and needles almost with the same pride a samurai might take in showing off his sharpened weapons.

In her “Pelle d’asino” (“Donkey hide”) exhibition at “Abitare il Tempo” in Verona in September 2006 she showed the importance of animal skin in her work by setting out the process she goes through when designing with leather. This consisted of displaying the study models of some rather complex projects, set out on a big table with Kartell containers holding balls of wool, skeins of thread, scissors, needles, pins, crochet hooks, and knitting needles. Alongside this she showed some of her leather-covered furniure pieces first before they had been covered, and then finished with her imaginative textile and leather patchwork upholstery. In this way her intention was to be clear that whilst her work can only be made with complex technologies, it has its roots in a world of art and craft. And in this work she never strays away from her “milanese” focus on finding a synthesis that rejects everything futile or redundant.

Design process Landscape collection, Rosenthal, 2008.

Design process Landscape collection, Rosenthal, 2008.

As a Spanish Basque woman she has an extrovert personality, generous in her use of musical, fluid words and gestures, and has a way of speaking softened by hispanic cadences. At the different universities she attended (principally at Milan Polytechnic, where she graduated) she made her own the lesson of the great Milanese masters, most importantly Achille Castiglioni, who taught her to take an interest in everything around her; and then Bruno Munari, from whom she learned that "one thing leads to another" as, for example, a bracelet that she found in a junk shop and which became her inspiration for a lamp (Caboche by Foscarini, their best seller). Remembering the supreme gift she was given by Tomás Maldonado – a lesson on comfort and its importance – she says “I always try to design objects that offer the type of comfort that will embrace every part of a person’s life".

She retains sharp memories of those formative years because she is in no doubt that whatever we do is the result of choices we made earlier, perhaps a long time ago, and that those choices were, in turn, the result of convictions we had adopted and made our own. “Nothing happens by chance. Even though in design the momentum of improvisation and the fluidity of the spontaneous gesture are always important, each project is the result of patiently putting things together".

“Doing design,” she says, “is like music that dances along.” Happy music, like fountains playing. Like Mozart: a music that gives pace to life.In the course of many commissions and designs she has always managed to make her own recognisable mark or rather, her tone. “Doing design,” she says, “is like music that dances along.” Happy music, like fountains playing. Like Mozart: a music that gives pace to life. Unlike the radicals, her aim as a designer is not to generate conflict or be provocative but to consider “the pleasure of using things” and give comfort. This again shows her feminine side, the expansive generosity that is part of her being.

“Expansive” is a word that not only suits her personality very well, but also her approach to design; not so much in terms of its physical form (even though we are indebted to her for having renewed the forms of many things, in important ways) but in terms of relating. Which brings us back to leather and animal skin. Those are the real interfacing, relating materials of her work: the personalising components through which her tone seems to breathe, just as it breathes through her own sensitive, varied skin every time she designs something, bringing out new objects and making them come alive.

Published in Experimenta 61.